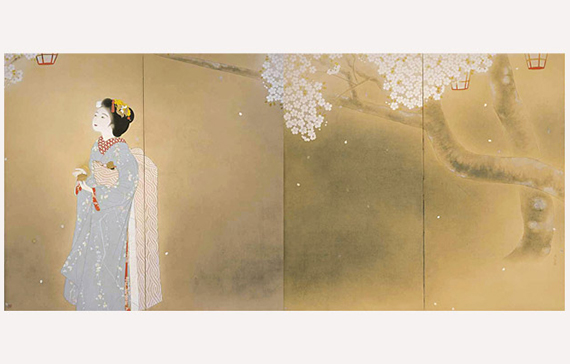

Discovery is somewhat of an exaggeration. In fact, Late Autumn is considered Uemura Shoen’s masterpiece and museums throughout Japan want the museum to loan it to them. But about 20 years ago, what I found when checking the catalogue detailing the paintings in the museum’s holdings prompted some questions. Such a catalogue typically provides information on the provenance of a work—the name of the work, the name of the person who donated the painting, when it became part of the museum’s holding, and so forth. But I found that many pages were missing from the catalogue. Perhaps, amid the confusion of war, it was not possible to perform a proper inventory. The Japanese Imperial Army requisitioned the museum building in November 1942. Although the museum was able to hold the Japanese Paintings from Kansai exhibition in one wing of the building, the overall situation was chaotic. Moreover, the U.S. Army requisitioned the museum building from October 1945 to 1948. The museum was unable to operate normally during these years. Consequently, the paintings featured in the Japanese Paintings from Kansai exhibition languished largely unseen for 50 years.

EN

EN