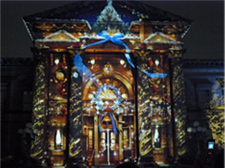

A building’s design reflects the client’s preferences and aspirations. This is certainly true of Nakanoshima Library.

For Nakanoshima Library the client was Kichizaemon Tomoito Sumitomo, the 15th head of the Sumitomo family. Traveling through Europe and the U.S. from April to November 1897 (30th year of the Meiji era), Tomoito was struck by the evident prosperity of commerce and industry as well as the managerial revolution underway. At the same time, he deepened his understanding of art, architecture, and other aspects of culture, including the lifestyles and mores of the upper echelons of European and American society. He was particularly impressed by the philanthropy of wealthy Europeans and Americans who were so generous in their support of institutions and activities beneficial to society. These experiences and observations bore fruit in his decision to build and endow the Nakanoshima Library.

In 1900 (33rd year of the Meiji era), Tomoito proposed his philanthropic scheme to the Osaka Prefectural Government. He would build a library for the benefit of the people of Osaka, donating the library building together with an endowment of 50,000 yen to support the institution. This was a pioneering philanthropic initiative in Japan. Warmly welcomed by the prefectural assembly, Tomoito’s proposal was unanimously approved.

It is revealing that Tomoito chose to donate the library rather than simply donate the funds for its construction. Tomoito’s personal involvement in the project reflects his commitment to the creation of an enduring institution, a cultural beacon in the commercial city of Osaka. Moreover, the artistic heritage that he had encountered while traveling abroad found eloquent aesthetic expression in the splendid building he commissioned in his native city.

The construction of Nakanoshima Library took three years, making it a rather lengthy project for its scale. The construction cost of 200,000 yen greatly exceeded the initial budget of 150,000 yen, which may well have reflected Tomoito’s uncompromising pursuit of quality and meticulous attention to detail.

EN

EN