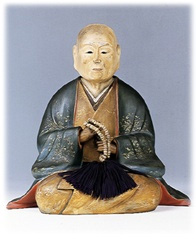

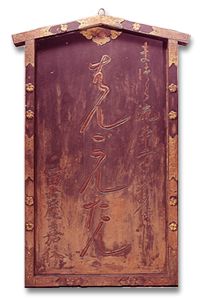

Masatomo Sumitomo wrote the Monjuin Shiigaki, known as the Founder’s Precepts, toward the end of his life to offer guidance on how a merchant should conduct business. Rather than offering a set of principles explicitly focused on the continuity and development of the House of Sumitomo’s business, the Monjuin Shiigaki, with its preamble and five precepts, consists guidelines pointing out the overriding importance of diligence and integrity in everything that a person undertakes. Below are the contents of the Monjuin Shiigaki.

Do your best prudently and meticulously, not only in business, but also in every aspect of your life.

- If items are offered to you at prices lower than the market prices, assume they are stolen goods unless their origin is known.

- Do not put anyone up for the night or accept anyone’s request to look after his belongings.

- Do not act as a broker or provide a guarantee for anyone you do not know.

- Do not sell or buy on credit.

- Whatever the person you are dealing with says, do not become short-tempered and argumentative. Instead, provide detailed explanations repeatedly.

EN

EN