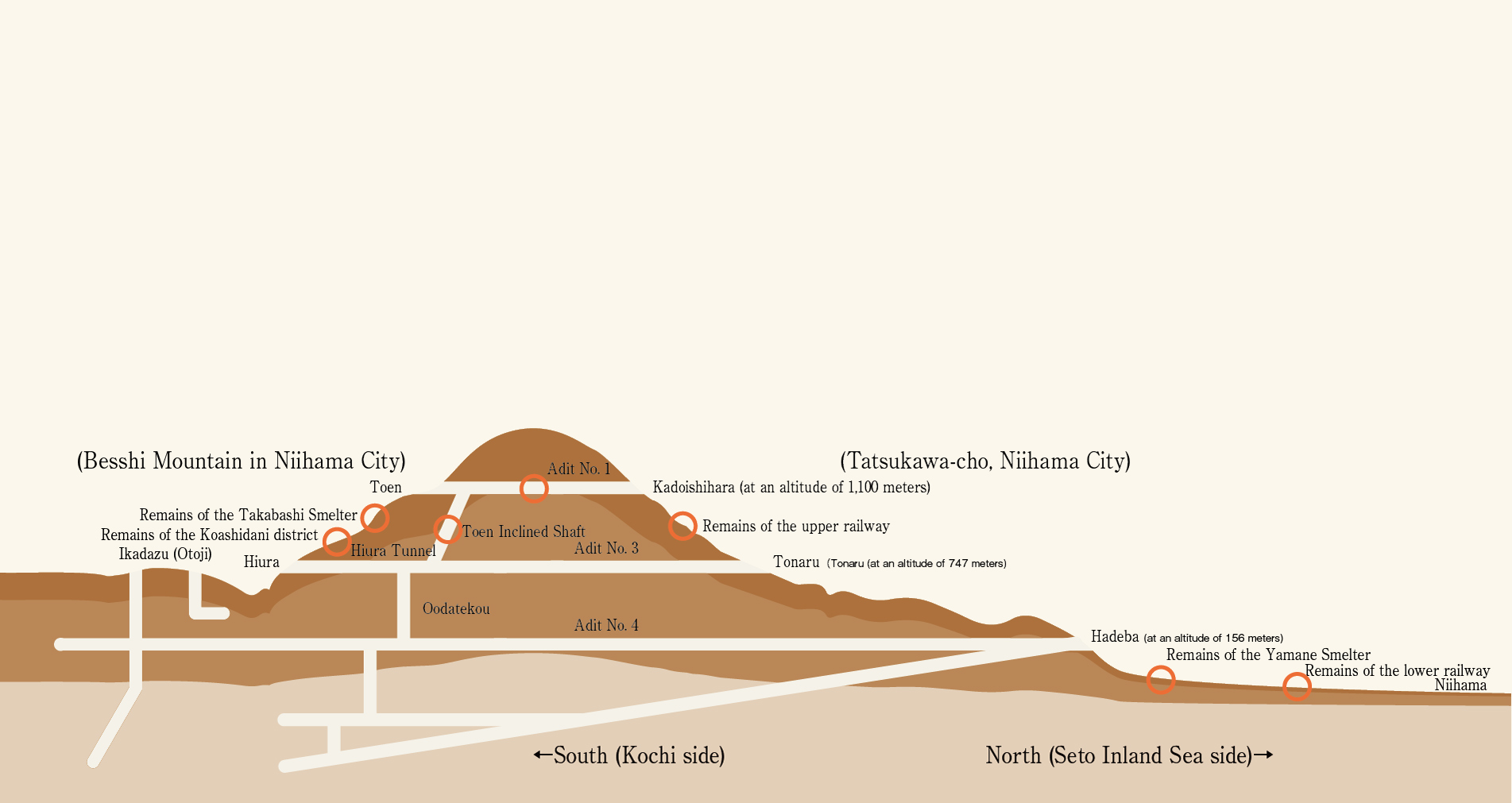

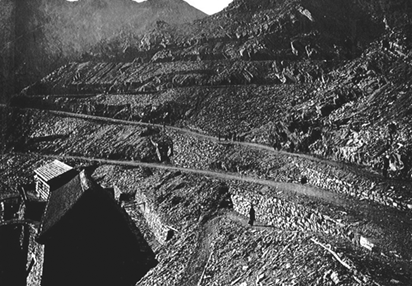

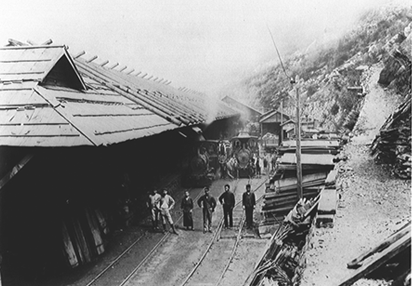

In 1874, Sumitomo hired French engineer Louis Claude Bruno Larroque in a bid to modernize operation of the copper mines. Some 180 years since their inauguration, the Besshi Copper Mines were grappling with several tough issues. Such deep shafts had been excavated that groundwater was constantly well up, causing a lot of trouble and constraining the miners’ freedom of action. The old-fashioned method was good enough for smelting rich ore with high copper content but not up to the task of smelting lower-grade ores with copper content of 3% or so, which meant such ores were left unexploited. Moreover, porters carried the ore to the foot of the mountain via a steep mountain pathway and so transportation was totally reliant on manpower.

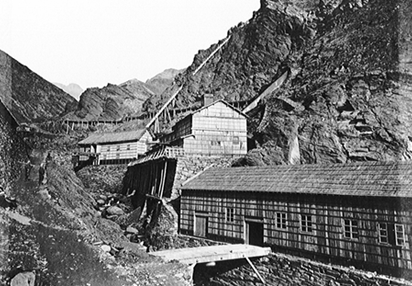

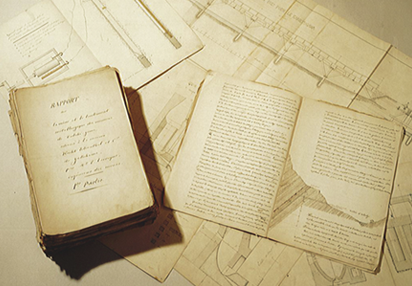

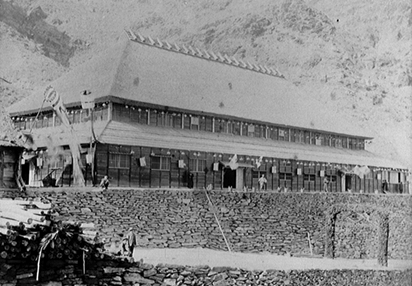

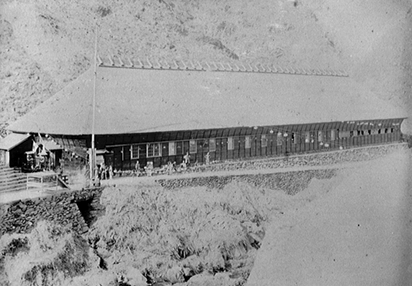

Larroque spent almost two years thoroughly analyzing the circumstances of the mines and prepared a report on modernization measures utilizing the latest know-how and technology. Based on Larroque’s masterplan, extensive modern facilities were constructed at Kyubesshi from 1876 onward. As a result, the output of the mines, which had been less than 6,000 tons in 1868, exceeded 50,000 tons in 1893, and the Besshi Copper Mines contributed greatly to the emergence of Japan as a formidable industrial power.

EN

EN