Overcoming financial difficulties

Sumitomo’s first project of the Meiji era was to modernize the cash-starved and debt-burdened Besshi Copper Mines. Former daimyo owed Sumitomo 180,000 ryo (1 ryo = 1 yen) and Sumitomo owed the government 88,500 ryo for rice supplied for the miners’ sustenance. While striving to collect loans and repay debts, in 1869 Saihei Hirosei issued private banknotes, known as yamaginsatsu, valid only within the Besshiyama area, in a move designed to improve liquidity.

In 1870, in order to secure funds for modernization of the Besshi Copper Mines, Hirose invested in Osaka Kawasekaisya, Japan’s first bank, and secured a loan. However, this company, whose investors included both the government and wealthy Osaka merchants, collapsed in 1873 under a mountain of bad debts. At the request of the investors, Hirose took charge of the liquidation, managing to collect a considerable amount of loans by 1877 for distribution to the investors.

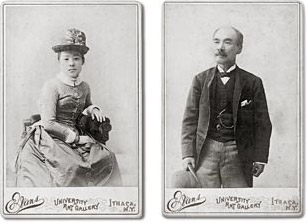

These photos were taken during their visit to Europe and North America in 1889.

EN

EN